I’m not an early riser. By the time I woke up on Friday, the world had already experienced one of the most massive outages in recent history courtesy of CrowdStrike. My phone was buzzing with missed calls, texts, and inquiries from CxOs and media asking what happened, why it happened, and what it means for the cybersecurity industry. I spent the rest of my day on calls while following stories about people flying with paper boarding passes, frustrated passengers at airports, happy employees who got an unexpected day off, and anxious, helpless, and angry admins on the frontlines of this outage. I also spoke to The Wall Street Journal and TechCrunch for their coverage of this story.

Incident Details and Response from CrowdStrike

Since the incident, we’ve learned that it was caused by a botched automated update from CrowdStrike, affecting only Windows machines, not Mac or Linux. We still don’t know why CrowdStrike didn’t catch this error before it reached millions of end users and bricked their devices. We’re patiently waiting for the root cause analysis (RCA).

The initial response from George Kutz, the CEO of CrowdStrike, was less than ideal. He downplayed the incident that crashed most Fortune 500 Windows devices with a blue screen of death (BSOD) and caused an estimated $1 billion in damage, referring to it as an “inconvenience.” Though he later apologized, the damage was done. People never forget the first response. It’s possible CrowdStrike didn’t initially realize the gravity of the situation. CrowdStrike has been working hard to help customers restore their systems and regain their trust. Shawn Henry, the chief security officer of CrowdStrike, has given the most empathetic response I've seen.

Broader Industry Implications

While the cybersecurity industry sees innovation from startups and smaller companies, it’s still dominated by a few large vendors, including CrowdStrike. Some vendors, like Palo Alto Networks, advocate for platformization, aiming for even greater consolidation. In the coming days, we’ll hear many stories about CrowdStrike’s engineering culture, business practices, and leadership. What’s evident is what we engineers have always known: systems with a single point of failure (SPOF) are extremely vulnerable if not managed properly. Just ask public cloud providers powering businesses worldwide. A stringent DevOps process, significant investment in site reliability engineering (SRE), gradual rollouts, canary zones, ultra-fast rollbacks, and state-of-the-art resiliency plans are essential. Unfortunately, CrowdStrike is not a native cloud company. Their primary product, an endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool, is installed on devices (endpoints) they secure. For Windows machines, this requires low-level highly privileged operating system access to install and run the Crowdstrike software agent called Falcon.

Source: Twiiter/X

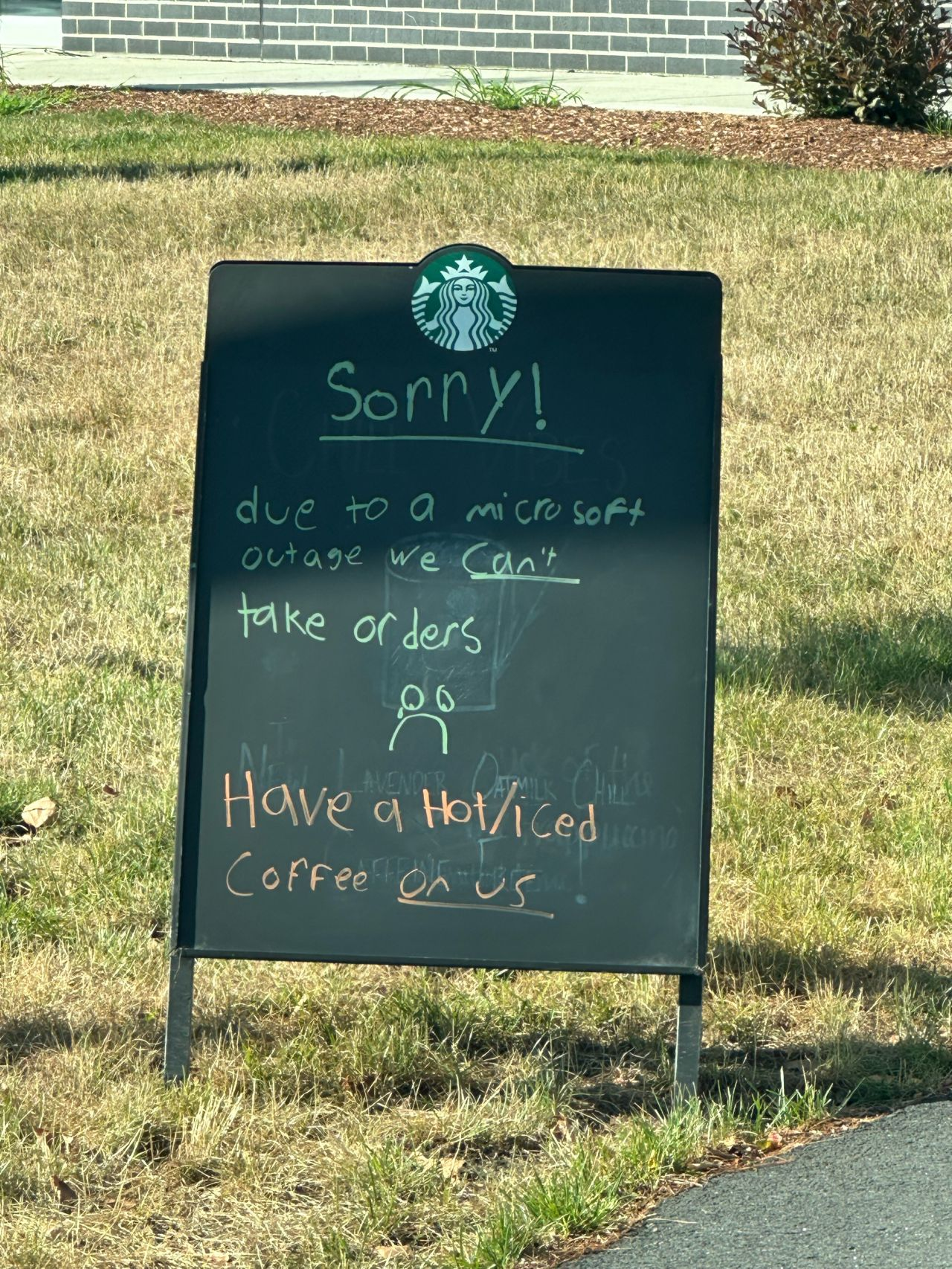

Microsoft’s Role and Customer Impact

Some might argue that this wasn’t Microsoft’s problem since they’re just an operating system provider. I argue the opposite. The fundamental design of Windows that requires such access was the primary reason CrowdStrike could push a botched automated update deep into the operating system without adequate checks by Microsoft. Customers using Mac machines weren’t affected because Mac, with its underlying Linux architecture, doesn’t allow the same level of access to third-party vendors, yet it provides the same functionality. Microsoft acknowledged the broad economic and societal impacts of this outage but called it "infrequent"; it’s like saying terrorism is infrequent—it doesn’t lessen the severity. In fact, the very infrequent nature of such incidents makes them hard to detect and protect against. The CxOs and system administrators I talked to are upset and angry. They’re reconsidering whether to keep automatic updates enabled, and many are actively considering moving away from Windows unless Microsoft addresses the underlying architectural flaws related to installing third-party agents.

Agentless Security and Future Directions

This incident also sparked a discussion on the agentless approach many cybersecurity solution providers are adopting, particularly in cloud environments and OT devices like industrial controllers and medical equipment. The cloud can be secured without running an agent, and OT devices are often too complex and proprietary for agent installation. We’ll likely hear more about achieving security without invasive methods, such as installing agents deep into operating systems. Additionally, there will be discussions on modernizing DevOps, air-gapping updates, and various efforts to balance security with business continuity.

A Wake-Up Call for the Industry

This happened to CrowdStrike, but it could easily have happened to any other EDR vendor with agents running on customers’ devices. It could also happen to non-cybersecurity vendors requiring deeper OS access, like screen-sharing software or asset management agents. This is a reckoning moment for an industry reexamining its dependencies on technology for business continuity. Many customers I spoke to didn’t have the disaster preparedness they needed, including tabletop exercises, disaster drills, and post-incident command centers. Post-breach or post-incident resiliency plans are non-negotiable. Airline customers won’t remember CrowdStrike, but they won’t forget being stranded at an airport staring at a blue screen of death, unable to get a boarding pass. You own your customer experience and need to control that, not your vendors.

- CrowdStrike, Palo Alto Networks duel over platforms vs. bundles

- CrowdStrike delivers strong Q1 amid cybersecurity platform debate

- Palo Alto Networks launches platform deals as it aims for cybersecurity share

- Palo Alto Networks Q3 solid, says customers into platform play

Looking Ahead

In the coming days, I look forward to a debate on:

- Architectural approaches for third-party agents requiring deeper operating system-level access

- Accountability of operating system vendors and third-party software vendors that can break devices causing significant business continuity challenges

- The concentrated cybersecurity landscape, platformization, and single point of failure